The Journal of San Diego History

SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY

Summer 1975, Volume 21, Number 3

James E. Moss, Editor

… it is well known that public improvements requiring the acquisition of large property must recede population; otherwise they are impossible.1

John Nolen

In 1908, John Nolen, a nationally respected landscape architect and city planner, wrote and illustrated a book, San Diego, A Comprehensive Plan For Its Improvement, primarily at the request of citizen George White Marston. Nolen wrote to Marston that San Diego “has no wide and impressive business streets, practically no open spaces in the heart of the city, no worthy sculpture.” As a solution, he proposed more open space for public use and the conversion of certain streets into boulevards, or prados, with large boulevards connecting the bayfront, civic center, and Balboa Park. Nolen warned that if the planning of San Diego’s growth “is haphazard you will lose many of the advantages that nature has presented to you as a free gift.”2

After 1908, a utilitarian-minded movement developed, centered on practical aspects of urban growth. As one observer noted, “Conspicuous among the champions of utilitarian planning was John Nolen, …architect and founding father of modern planning in America….” Nolen not only concerned himself with development of a “City Beautiful,” but also concentrated on things such as “faulty street arrangement, the condition of waterfronts, [and] the uncoordinated transportation system….”3

After 1908, a utilitarian-minded movement developed, centered on practical aspects of urban growth. As one observer noted, “Conspicuous among the champions of utilitarian planning was John Nolen, …architect and founding father of modern planning in America….” Nolen not only concerned himself with development of a “City Beautiful,” but also concentrated on things such as “faulty street arrangement, the condition of waterfronts, [and] the uncoordinated transportation system….”3

Historians have labeled the concern for better planned cities as part of the Progressive Movement. Samuel P. Hays expressed the dilemma that must have been obvious to John Nolen, George Marston, and other Americans at the turn of the century: “How can the technical requirements of an increasingly complex society be adjusted to the need for the expression of partial and limited aims?”4

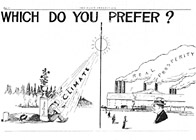

In order to implement Nolen’s planning advice, Marston ran for mayor of San Diego in 1913 and again in 1917, tasting defeat both times. The campaign of 1917 was especially provocative, for in that year Louis Wilde, advocating greater growth and more “smokestacks” for the city, soundly defeated Marston, who had been identified by Wilde’s faction as being opposed to growth and derisively labeled as a “geranium.” The 1917 mayoralty campaign, therefore, anticipated future struggles between the advocates of growth and those of quality control.

In order to implement Nolen’s planning advice, Marston ran for mayor of San Diego in 1913 and again in 1917, tasting defeat both times. The campaign of 1917 was especially provocative, for in that year Louis Wilde, advocating greater growth and more “smokestacks” for the city, soundly defeated Marston, who had been identified by Wilde’s faction as being opposed to growth and derisively labeled as a “geranium.” The 1917 mayoralty campaign, therefore, anticipated future struggles between the advocates of growth and those of quality control.

At the turn of the century, San Diego, already incorporated for fifty years, boasted a city population of around 17,700. During the following twenty years, the city experienced the Industrial Workers of the World struggling for free speech and worker unity in 1912, the opening of the Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park in 1915, and the completion of the San Diego and Arizona railroad in 1919. Commercial and military harbor development also began to grow during the period.5

By 1920, San Diego’s city population numbered 74,683. In that year, the United States Census gave the following occupational breakdown of population ten years of age and over:6

| total work force | 31,037 |

| approximate breakdown in United States 1920 Census: | |

| Transportation (rails, trucks, road repairs, etc.) | 2,586 |

| trade (retail dealers, salesmen, etc.) | 5,713 |

| public service (city officials, police, firemen. etc.) | 1,607 |

| professional service (teachers, lawyers, doctors, etc.) | 3,097 |

| domestic and personal service (waiters, barbers, laundry workers, etc.) |

4,478 |

| clerical categories | 2,896 |

| agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry | 1,977 |

| mineral mine workers | 217 |

| manufacturing and mechanical industries (factories, construction, skilled laborers, trades, etc.) |

8,066 |

San Diegans could boast of a tire company, munitions plant, packing industry in agriculture and fishing, a fishing fleet, and a large naval establishment.7

At the time of the mayoralty election of 1917, population and job opportunities were expanding, but it was apparent that if San Diego wanted to compete with San Francisco, and particularly with its neighboring city of Los Angeles, it needed more investment and building. Those citizens who wanted to compete for more rapid expansion willingly sacrificed certain aspects of city planning. The less competitive elements of the city believed in a controlled growth that would not exclude opportunities, but would carefully scrutinize the long range effects of economic growth. The mayoralty campaign of 1917 illumined these issues.

George Marston and Louis Wilde were the prominent figures in the campaign, Marston representing beautification, aesthetic considerations, and conservative planning, while Wilde campaigned for greater business development and more “smokestacks.”

George Marston was an early resident of San Diego, arriving from Wisconsin in 1870. J.D. Nash, general store proprietor, gave him his first job in 1872. Marston worked diligently, so that by 1917 he was a respected, independent businessman, and owner of a retail business that employed 247 people. In addition to his retail business, he was extremely civic minded, having served as Fire Commissioner, Park Commissioner, City Councilman, and unsuccessful candidate for mayor in 1913.8

George Marston was an early resident of San Diego, arriving from Wisconsin in 1870. J.D. Nash, general store proprietor, gave him his first job in 1872. Marston worked diligently, so that by 1917 he was a respected, independent businessman, and owner of a retail business that employed 247 people. In addition to his retail business, he was extremely civic minded, having served as Fire Commissioner, Park Commissioner, City Councilman, and unsuccessful candidate for mayor in 1913.8

Marston was also instrumental in the development of Balboa Park and in planning for the 1915 exposition. In 1903, along with several architects, Marston had translated “the barren wilderness” of Balboa Park, noted a local historian, “into a spot of perennial beauty by means of a well conceived, harmonious, unified design for its artistic development.”9

In addition to these activities, Marston was president of the San Diego and Eastern Railroad Company, which was attempting to secure for San Diego a direct connection with the east. In 1906 John D. Spreckels secured control of the company and successfully completed the line in 1919, known as the San Diego and Arizona Railroad.10

In the 1913 mayoralty campaign, Marston had favored planned expansion of the city, completion of the railroad to Arizona, harbor improvements, and rapid building for the California-Panama Exposition. In the development of these areas, he claimed a scientific approach: “I stand for a systematic, scientific business administration and for a form of city government which employs trained experts to run its departments under civil service rules.” Perhaps Marston was a visionary, a man ahead of his time, in trying to prevent unlimited growth and expansion. Writing in the 1950s, Shelley J. Higgins observed that “Marston’s platform was derided as limiting San Diego development to homes and flowers….Nowadays, perhaps, Marston might have rallied popular support on an anti-smog basis.”11

In 1913, Louis Wilde, a prominent banker and not yet a declared politician strongly endorsed Marston’s opponent, Charles F. O’Neall. Said Wilde: “O’Neall is progressive, not narrow, conservative….Mr. Marston …means well but he has not got it in him to do broad things for anybody….”12

Louis Wilde was born in lowa City, Iowa, from where he moved to St. Paul, Minnesota. There, he engaged in farm land dealings and in merchandising. He then moved to Texas, invested wisely in oil lands, and became a financial success. In 1902 he came west to Los Angeles and then moved to San Diego in 1903, where he was to stay for the next eighteen years. In San Diego, Wilde gained a reputation as a hard-driving financier and banker, never being accused of lack of vigor in speech and deed. He was the first president of the Citizens Savings Bank and the American National Bank, both founded in 1904. He also started and became the first president of the United States National Bank. Julius Wangenheim, a San Diego businessman and Marston supporter, later described Wilde in scathing terms. Wilde, said Wangenheim, “started a bank, launched a telephone company, engineered the Grant Hotel, and messed up everything he touched.”13

As Wilde’s interest in his adopted city became stronger, he increasingly clashed with Marston and others who favored a cautious approach to city growth. Wilde’s drive and energy and his opposition to Marston’s philosophy prompted him to seek the office of mayor in 1917. He labeled Marston as his adversary standing in the way of progress. A 1918 letter to the San Diego Sun related Wilde’s views on the business attitude prevailing in the city:

If a live wire comes to town. he is put in close proximity to the high powers of invisible government and induction sets in the first time he undertakes to do anything unusual in trying to build a shipyard or bring in a manufacturer or to finance a public building, or dares to disturb the seagulls where the lilies-of-the-valley are to be planted for posterity, right then and there he is notified by the Pro-Geranium and Amalgamated Society of Ancient Quietus that he is not wanted in these parts.14

In his bid for the mayoralty, Marston had the support of John D. Spreckels, a name that stood above others in terms of money and influence and a man who was a member of the Spreckels sugar family of San Francisco. In 1887, Spreckels had sailed his yacht, the Lurline, into San Diego harbor. Shortly thereafter, millions of dollars in investment money flowed into the city, and Spreckels soon dominated the political and financial life of San Diego. His holdings included two of the city’s three daily newspapers, the San Diego Union and the Evening Tribune, the street car system, the San Diego and Coronado ferry company, ranch properties, three large business buildings, and for a time the city water system. One of his crowning achievements was the completion of the San Diego and Arizona Railroad, which meant the construction of 144 miles of line from San Diego to E1 Centro in Imperial Valley at a cost of eighteen million dollars.15

With a man of Spreckels’ ability, one could assume Marston had an excellent ally, but Spreckels did not push hard for Marston’s concept of city planning. As historian Richard Pourade has observed, “though Spreckels had supported Marston for mayor in the ‘geraniums vs. smokestacks’ campaign of 1917, his influence was not always exerted on the side of community-wide planning. He had many development projects of his own.” Indeed, although the Spreckels newspapers endorsed Marston, they also entertained many points of view, including the idea that “geographically, San Diego is situated to become a manufacturing city.”16

Further, in January, 1917, a San Diego Union headline claimed that “Commerce Has First Call Upon City’s Waterfront.” Beautification and public recreation received secondary importance. In the article that followed, James D. Eaton, a writer for the Union, sarcastically cast the city beautifiers as,

those who have already made their money and who wish to sacrifice the opportunities of others by burdening the people with the task of building a Garden of Eden which none but the wealthy could live in and enjoy….The bay front belongs to commerce and the city’s beautifiers should roll their hoops in another direction…. when it comes right down to brass tacks, it is better to have a fairly pretty commercial city which is prosperous, than to have an unusually beautiful city whose citizens have nothing in their pockets.17

The Union did not feature equivalent articles in defense of a city plan such as Nolen’s.

Given the Union’s point of view, why, then, did Spreckels endorse Marston? One hint came in the summer of 1917, when the Union filled pages with praise for San Diego’s climate and for the adjoining beach resorts which had sprung up to exploit tourist possibilities. Spreckels owned large holdings in beach realty, including Coronado Tent City, which housed visitors to the beach during the summer. He began developing beach properties in Mission Beach and La Jolla after his success on Coronado. Spreckels might have concluded that tourists would find Marston’s “beautiful city” more attractive than Wilde’s “belching smokestacks.” In addition, Marston’s department store was by far the biggest advertiser in the Union and Tribune, which provided another reason for friendship and political support.

The political advertising campaigns waged in the newspapers were revealing and described the issues, events, and opinions better than did the editorials. A certain advertisement, baiting Wilde. inquired, “Mr. Wilde — 30,000 voters demand to know how you could make good on your ‘Mysterious Smokestacks’ slogan?” The advertiser wondered where the smokestacks would come from, but received no direct answer.18

The political advertising campaigns waged in the newspapers were revealing and described the issues, events, and opinions better than did the editorials. A certain advertisement, baiting Wilde. inquired, “Mr. Wilde — 30,000 voters demand to know how you could make good on your ‘Mysterious Smokestacks’ slogan?” The advertiser wondered where the smokestacks would come from, but received no direct answer.18

The Wilde advertisers ignored these challenges. Instead, they considered the best defense to be an offense. Further, they were confident that Wilde had captured the imagination of the city by his smokestack image. So they concentrated on Marston’s image as “Geranium George,” identifying him completely with flowers, sunshine, and total complacency: “Which do you prefer, progress and prosperity or dreams and daisies?” asked one political ad.19

Support for Marston came from a large segment of the business community, including the Civic Association, Citizens Committee of local businessmen, and the Municipal League. Despite this impressive support, Wilde’s campaigners continued to label Marston as anti-business. Perhaps Marston’s prestigious supporters did not define their candidate’s position clearly enough, or perhaps they could not cope with the distortions of Wilde’s campaign. Marston did favor growth together with sound planning, and on one occasion he sought to clarify his position:

I want to see a planned and comprehensive improvement of the whole bay shore so that it will serve the purposes of commerce, manufacturing and the United States Navy. Its primary importance is commercial…. If elected Mayor, I would encourage the industrial development of the city and county along the lines of manufacturing, commerce and horticulture.20

Three smaller newspapers with limited circulations sided with Wilde. They emphasized his promise for more industry while portraying Marston as a well-intentioned flower lover. The Daily Smokestack printed the following booster song for Wilde:

San Diego needs a mayor who will bring prosperity,

Who will help to build up factories in this city by the sea.

Oh, we love to have the tourists come, in our sunshine to bask,

But we need some smokestacks:

Give us work: a chance is all we ask.Yes, we, too, enjoy the flowers in this climate without par,

But a steady job that pays us well we need that more by far,

For our children want to go to school as well clad as the rest.

Let’s elect a man, “who knows the game:”

Trust him to do his best.21

The Labor Leader, also pro-Wilde, labelled the campaign as the “silkies against the woolen socks,” claiming that “Every big interest in San Diego is backing Mr. Marston.” With this type of propaganda, Wilde emerged as a worker’s hero in attempting to entice more industry and thus more jobs to the area.22

The Marston faction continued calling Wilde’s promise of more industry a bluff. An advertisement in the Union inquired, “how as mayor would Wilde be in a better position to secure smokestacks than as the President of a bank? Why hadn’t he produced a single smokestack in his fifteen years in San Diego?”23

The Wilde campaigners in turn claimed that “Marston admits that even his idea of a city beautiful may be but a figment of the imagination.” They further argued that “Marston is content with a beautiful horizon and an unsullied landscape.”24

Mary Gilman Marston, daughter of George Marston, later recalled the campaign of 1917 as an exciting affair in San Diego, but also one that wearied her father because of the name-calling and slandering. The family, she said, laughed at the “Geranium George” label. She also appreciated the fact that her father had not responded in kind, even though he was distressed at the distortions and surprised by the vehemence of the opposition.25

Election day, April 3, 1917, may have been clear and bright, but the results brought gloom to the Marston camp. Wilde won 12,918 to 9,167. As in 1913, Marston had to be content to work for his city goals as a private citizen. The pro-Wilde San Diego Herald described the election as a great one:

…the greatest ever held in San Diego. Besides the determination to make this an industrial city, it proved that the people of San Diego were able to overthrow the old political machine which has so long dominated the city.26

The growth of San Diego continued. As mayor, Wilde sought more industry and referred to Los Angeles as a great city and a model to emulate, “bidding welcome to all capital and enterprising men.” In contrasting the two cities, Wilde said “Los Angeles is full of youth, vision, imagination, optimism, curiosity, boosters, and brains. San Diego is full of old tight-wads, pessimists, vacillating, visionary dreamers….” Wilde left San Diego for Los Angeles in 1921 when his second term as mayor expired, declaring that it was “a thankless job.” He died three years later.27

Marston, however, had a commitment to San Diego and continued living and working in the city until his death in 1946. He remained active in civic affairs throughout the 1930s, when he officially retired from business, remaining a director in his merchandising firm. In 1939, at age eighty-eight, Marston was still busy proposing city plans. That year. the San Diego County Planning Commission “adopted a resolution favoring George W. Marston’s proposal to remove unsightly billboards and ugly structures from the areas bordering the highway South from the Orange County line.” The resolution described the plan as a step in the proper direction and a part of a long-range proposal to make San Diego one of the most beautiful cities and counties in the country.28

George Marston’s belief in planned and cautious urban growth survived his death in 1946, for the Marston family continued the commitment. In September, 1974, Donald Appleyard and Kevin Lynch, urban planners, wrote and illustrated a report to the City of San Diego, entitled Temporary Paradise? A Look at the Special Landscape Of The San Diego Region. This report was prepared through a grant from the Marston family and dealt with the further utilization of the San Diego region for maximum use and enjoyment while keeping a high standard of beauty, cleanliness, and planning. The following statement capsulized the authors’ concern for San Diego:

This bold site, its openness, its sun and mild climate, the sea, the landscape contrasting within brief space are (along with its people) the wealth of San Diego. They are what have attracted settlers to the place and still attract them. They must not be destroyed.29

George Marston would have been pleased. In the early twentieth century, a period of blossoming progressive movements and urban consciousness, George Marston was the first to recognize the need for careful city and county planning.

1. John Nolen, San Diego. A Comprehensive Plan For Its Improvement (Boston: George N. Ellis Co., 1908),90.

2. Carl H. Heilbron, History of San Diego County (San Diego: The San Diego Press Club, 1936), 131 (biographical section). Richard Pourade, The History of San Diego (VI vols.. San Diego: Union Tribune Publishing Company, 1965), V, 100, and VI, 27. John Nolen. Letters of, 1907-1909, San Diego Historical Society, Serra Museum, San Diego.

3. Roy Lubove, “progressivism, Planning and Housing,” in The Challenge of the City, 1860-1910. ed. by Lyle W. Corsett (Lexington, Raytheon Education Company, 1968), 84.

4. Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency (The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920). (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1959), 276.

5. San Diego City Directory, (San Diego: San Diego Directory Co., 1917), S6.

6. Fourteenth Census of the United States (VII vols., Washington: Government Printing Office, 1923), V, 315-317.

7. Pourade, The History of San Diego, VI, 7-9.

8. Heilbron. History of San Diego County, 130 (biographical section).

9. Clarence Alan McGrew, City of San Diego and San Diego County (II vols., New York: The American Historical Society, 1922), I, 309.

10. Heilbron, History of San Diego County, 130 (biographica1 section).

11. “George M. Marston-The Candidate. ” a political pamphlet in the 1913 mayoralty campaign folders. San Diego History Center, Shelley J. Higgins. The Fantastic City San Diego, (San Diego: City of San Diego. 1956). 292

12. Pourade. The History of San Diego. V, 172.

13. McGrew. City of San Diego and San Diego County. I, 186, 308. Julius Wangenheim, “An Autobiography (concluded),” California Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XXXVI, June, 1957, No. 2, 155.

14. San Diego Sun. May 1. l918.

15. Frederick L. Ryan, The Labor Movement in San Diego: Problems and Development from 1887 to 1957 (San Diego: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, Division of Business Administration, San Diego State College, 1959), 9. Pourade, The History of San Diego. VI, 11. McGrew, City of San Diego and San Diego County, I, 169.

16. Pourade, The History of San Diego, VI, 29. San Diego Union, January 1, 1917.

17. San Diego Union, January 21, 1917.

18. Ibid, March 29, 1917.

19. Ibid, January 21, 1917.

20. Ibid, March 15, 1917.

21. The Daily Smokestack. April 2, 1917.

22. The Labor Leader, March 30, 1917.

23. The San Diego Union, March 2, 1917.

24. The Daily Smokestack. April 1, 1917.

25. Conversation with Mary Gilman Marston: 6:30 p.m., August 5. 1974. 3525 7th Street, San Diego.

26. San Diego Herald, April 6. 1917.

27. San Diego Sun, May 1, 1918. McGrew, City of San Diego and San Diego County, I, 232.

28. San Diego Sun, August 27, 1939.

29. Donald Appleyard and Kevin Lynch, Temporary Paradise? A Look At The Special Landscape Of The San Diego Region. September, 1974. San Diego Historical Society.

Uldis A. Ports was graduated in 1964 from San Diego High School, where he was Student Body President. He studied at San Diego State University and earned Bachelors degrees in Political Science and History. After college he served as a Legal Yeoman (secretary) in the United States Navy. He is currently working on his Master’s degree in History at San Diego State University. His article published here won an Honorable Mention at the San Diego Historical Society’s 1974 Institute of History.

Illustrations are from the Historical Collections, Title Insurance and Trust Company, San Diego, and the San Diego History Center.