History of San Diego, 1542-1908

PART FOUR: CHAPTER 4: Water Development

The question of an adequate supply of water for San Diego always has been one of the most vital problems in the life of the place. During the short life of “Davis’s Folly,” or “Graytown,” and for some time after Horton came the inhabitants depended upon water hauled from the San Diego River. The early settlers still remember paying Tasker & Hoke twenty-five cents a pail for this water. After that, they were for some time dependent upon a few wells. An effort to find an artesian supply began in 1871. A well was sunk by Calloway & Co. in which some water was found at a depth of 250 feet. They asked for city aid to enable them to continue boring, but the proposition to issue $10,000 city bonds to carry on the work was defeated at an election held in July, 1872. The well in the court house yard furnished a good supply, which was used to some extent for irrigation. In 1873 a well was completed at the Horton House, which gave great satisfaction and was thought to demonstrate that “an inexhaustible supply of good water exists at but a comparatively trifling depth, which can be reached with little expense.” The well which Captain Sherman sank in the western part of his new addition, was also an important factor.

The town soon outgrew the possibility of dependence upon wells, early in its first boom, and in 1872 San Diego’s first water company was organized. This was the San Diego Water Company, incorporated January 20, 1873. The principal stockholders were: H. M. Covert and Jacob Gruendike; the incorporators were these two and D. W. Briant, D.O. McCarthy, Wm. K. Gardner, B. F. Nudd, and Return Roberts. The capital stock was $90,000, divided into 900 shares of $100 each. The term of the incorporation was fifty years from February 1, 1873. H. M. Covert was the first president.

The first works of this company were artesian wells and reservoirs. They bored a well in Pound Canyon, near the southeast corner of the Park, and found water, but at a depth of 300 feet the drill entered a large cavern and work had to be abandoned. The water rose to within 60 feet of the surface and remained stationary. They then sank a well 12 feet in diameter around the first pipe, to a depth of 170 feet, and from the bottom of this second boring put down a pipe to tap the subterranean stream. The large well was then bricked up and cemented. It had a capacity of 54,000 gallons per hour. Two small reservoirs were also constructed, one at 117 feet above tide water, with a capacity of 70,000 gallons, and the other more than 200 feet above the tide, with a capacity of 100,000 gallons. The water was pumped from the 12-foot well into these two reservoirs. Such were San Diego’s first waterworks. In March, 1874, the Union said with pride:

“About 18,000 feet of pipe will be put down for the present. Pipe now extends from the smaller reservoir down Eleventh and D, along D to Fifth, down Fifth to K, along K to Eleventh, and will also run through Ninth from D to K and from Fifth along J to Second. The supply from this well will be sufficient for 30,000 population and is seemingly inexhaustible.”

But notwithstanding this confidence, in a few years the water supply in Pound Canyon was found to be inadequate, and it was determined to bring water from the river. In the summer of 1875 the company increased its capital stock to $250,000 for the purpose of making this improvement. A reservoir was built at the head of the Sandrock Grade, on University Heights. The water had to be lifted several hundred feet from the river to the reservoir, and this pumping was expensive. In order to avoid this expense and improve the service, the company drove a tunnel through the hills, beginning at a point in Mission Valley below the new County Hospital and coming out on University Avenue near George P. Hall’s place. The water was piped through this tunnel, which is still in a fair state of preservation. A new reservoir was built at the southwest corner of Fifth and Hawthorne Streets; and these works constituted the San Diego water system until the pumping plant and reservoir at Old Town were constructed. This old reservoir gave sufficient pressure for the time being, and it was not then believed the high mesa lands would ever be built upon.

In the fall of 1879 the papers note that the water mains had been extended down K Street as far as the flour mill and thence up Twelfth to the Bay View Hotel. Early in 1886 the long delayed work on the river system, near Old Town, was resumed. From numerous wells in the river bed, the water was pumped into the large reservoir on the hill. At this time the company also made many extensions and laid new pipes for almost the entire system. The pumps installed had a capacity of 6,600,000 gallons per twenty-four hours. There are four covered reservoirs with a total capacity of 4,206,000 gallons. A standpipe was placed on Spreckels Heights, 136 feet high and 36 inches in diameter. The top of this standpipe was 401 feet above tide, and it regulated the pressure all over the city. According to the engineer’s statement, about 30,000,000 gallons were pumped during each month of the year 1888. The pipe lines in January, 1890, exceeded 60 miles and had cost $800,000. There were 185 fire hydrants connected, for which the company received $100 each per annum.

The next large undertaking in the way of water development was that of the San Diego Flume Company. This project originated with Theodore S. Van Dyke and W. E. Robinson, who worked upon it for some time before they succeeded in interesting anyone else. Then General S. H. Marlette became interested and these three associates secured the water rights needed for the development. In 1885, they planned to form a corporation, to be called the San Diego Irrigating Company, but for some reason the plan failed. The promoters continued to work indefatigably, however, and finally succeeded in enlisting the interest of George D. Copeland, A. W. Hawley, and a few others, and soon were in a position to incorporate. The articles of incorporation were filed in May, 1886. Besides those mentioned, the following were incorporators: Milton Santee, R. H. Stretch, George W. Marston, General T. T. Crittenden, Robert Allison, J. M. Luco, and E. W. Morse.

Sufficient money was paid in to start the work. Copeland became President, Robinson Vice-President, and Stretch Engineer. Captain Stretch served about six months and did some of the preliminary work. He was succeeded by Lew B. Harris, who served about a year, and then J. H. Graham became the engineer and remained until the work was completed. The capital stock was $1,000,000, divided into 10,000 shares of $100 each.

The difficulties encountered were many. There was an inefficient contractor whose men the company was compelled to pay. It was asserted that the flume encroached upon an Indian reservation, and there was frequently a lack of funds. Their means becoming exhausted, some of the original incorporators were obliged to step out. Copeland became manager in place of Robinson, and Morse president in place of Copeland. Later, Bryant Howard became president and W. H. Ferry superintendent, and these two men saw the work completed.

This great pioneer undertaking was organized and carried out by far-seeing, courageous men, for the purpose of irrigating the rich lands of El Cajon Valley and also of bringing a supply of water to San Diego. Incidentally, but quite as important, they were aware that they were making a demonstration of the agricultural possibilities of San Diego’s derided back country. There were a few citizens who understood the importance of the undertaking and watched the course of events with almost breathless interest. But the majority were too busy with real estate speculations to be much concerned—at least, this was true of the floating population of newcomers. Van Dyke writes pointedly: “The writer and his associates who were struggling to get the San Diego River water out of the mountains to give the city an abundant supply, and reclaim the beautiful tablelands about it, were mere fools ‘monkeying’ with an impracticable scheme, and of no consequence anyhow.”

DEDICATION OF THE SAN DIEGO FLUME. The man at the extreme right is Governor Waterman. The man in the second row wearing a straw hat is W. E. Robinson, one of the originators of the enterprise.

On February 22, 1889, the completion of the flume was celebrated in San Diego, most impressively. There was a street parade over a mile long, and a display of the new water. A stream from a 1¾ inch nozzle was thrown 125 feet into the air, at the corner of Fifth and Beech Streets, and at the corner of Fifth and Ivy, another one 150 feet high, to the admiration of the citizens. There were 19 honorary presidents of the day on the grand stand. Bryant Howard, M. A. Luce, George Puterbaugh, Hon. John Brennan of Sioux City, Iowa, D. C. Reed, and Colonel W. G. Dickinson spoke, and letters and telegrams from absent notables were read.

It is really a pity to have to spoil the story of the celebration of such an achievement, with a joke, but—the truth is, the water in the pipes at the time was not the Flume Company’s water, at all. The Flume Company had placed no valves in their pipes, and, consequently, when they turned the water on, it was airbound and the water advanced very slowly. When the day for the celebration came, the water being still several miles away, the officers of the San Diego Water Company quietly turned their own water into the pipes, and had a good laugh in their sleeves while listening to the praises the people lavished on the fine qualities of the “new water.” The Flume Company’s water arrived three weeks later.

The flume emerges from the San Diego River a short distance below the mouth of Boulder Creek, and proceeds thence down the Capitan Grande Valley to El Cajon Valley, about 250 feet from the Monte. From this point the flume curves to the east and south of El Cajon, at a considerable elevation. From El Cajon, the flume is brought to the city by the general route of the Mesa road. The total length of the flume proper is 35.6 miles. The reservoir is an artificial lake on the side of Cuyamaca Mountain, about fifty miles from San Diego, at an elevation of about 5,000 feet. Its capacity is nearly 4,000,000,000 gallons. It is formed by a breastwork of clay and cement, built across the mouth of a valley, forming a natural basin.

The construction of this flume exerted a very important influence in bringing on and sustaining the great boom, although it was not completed until after the close of that episode. The officers at the time of its completion. were: Bryant Howard, president; W. H. Ferry, vice-president and manager; L. F. Doolittle, secretary; Bryant Howard, W. H. Ferry, M. A. Luce, E. W. Morse, and A. W. Hawley, directors. These men are entitled to the credit of being the first to carry to a successful conclusion a scheme of development of the water resources of San Diego County, upon a large scale.

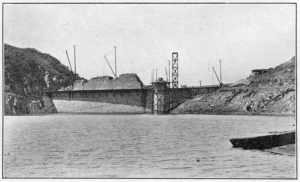

The construction of the Sweetwater Dam was begun November, 1886, and completed March, 1888, under the well-known engineer, James D. Schuyler. The Dam alone cost $225,000 and the lands used for reservoir site I7. .9,000 more. The original investment in the system of distribution exceeded half a million dollars. The reservoir stores 7,000,000,000 gallons and supplies National City Chula Vista, and a small area of land in Sweetwater Valley.

The Otay Water Company filed its articles of incorporation March 15, 1886, its declared object being to irrigate the Otay Valley lands and the adjacent mesa, and E. S. Babcock being the principal owner. In 1895 he sold a half interest to the Spreckels Brothers and the name of the corporation was changed to the Southern California Mountain Water Company. Later, the Spreckelses became sole owners. This company has an important contract under which it now supplies the city with its entire water supply. Its storage dam is at Moreno and its pipe line was extended to the city reservoir and the delivery of water commenced in the summer of 1906.

E.S. BABCOCK. Who came to San Diego in 1884 to hunt quail and remained to influence events more powerfully than anyone since Horton. A man of big conceptions and restless enterprise, he founded Coronado, engaged assiduously in water development, and was identified with numerous public utility corporations. Moreover, he it was who interested John D. Spreckels in local enterprises and thereby started as series of developments which is still unfolding to the immense advantage of the city and region.

The San Diego Water Company was incorporated in 1889, and in 1894 the Consolidated Water Company was formed for the purpose of uniting the San Diego Water Company and the San Diego Flume Company under one ownership. The Consolidated acquired by exchange of securities all the stock and bonds of both the water and the flume company. On July 21, 1901, the system of distribution within the city limits became the property of the municipality, a bond issue of $600,000 having been voted for its acquisition. The city obtained its supply from the pumping plant in Mission Valley until August, 1906, when its contract with the Southern California Mountain Water Company went into operation. Under the terms of this contract, the city obtains an abundant supply of water from mountain reservoirs at a price of four cents per thousand gallons, the water being delivered to its mains on University Heights.

The water question has been from the beginning a prolific source of controversy between the people and various corporations, and every important stage of its evolution, from the day of the earliest wells to the time when the great Spreckels system was sufficiently developed to meet the present demands, was marked by acrimonious discussion and sharp divisions in the community. The Spreckels contract was not approved by public opinion until an unsuccessful effort had been made to increase the city’s own supply by the purchase of water-bearing lands in El Cajon Valley and the establishment of a great pumping plant at that point. The municipal election of 1905 turned largely upon this issue. It resulted in the election of a mayor favorable to the El Cajon project, with a council opposed to it. A referendum on the subject revealed a curious state of the public mind. A majority favored the purchase of the lands, but opposed their development. The majority in favor of buying lands fell short of the necessary two-thirds, however, and the city government then turned to the Southern California Mountain Water Company as the only feasible means of creating a water supply to meet the needs of a rapidly growing city.

The mayor vetoed the contract with the Spreckels company when it first came to him from the council, urging that it be revised in such a way as to put its legality beyond all possible question (the contract was for a period of ten years, while the city attorney advised that it could legally be made for only one year at a time), and also to reserve the city’s right to operate its pumping plant in Mission Valley sufficiently to keep it in condition to meet an emergency. The council promptly passed the contract over the mayor’s veto, whereupon it was signed by the executive. The act was followed by the rapid completion of the pipe line to the city and the construction of an aerating plant on University Heights.

C.S. ALVERSON. To whom the public and the government is largely indebted for the exact knowledge concerning the water resources of the western slope of San Diego County, which he has studied for twenty years.

The consummation of this contract ended the long struggle for water and marked the beginning of a new epoch in the city’s life. This fortunate result was not due to the fact that the contract was made with any particular company, nor to the fact that it brought water from any particular source. It was due to the fact that the people of San Diego had obtained a cheap and reliable water supply adequate to the needs of a city three or four times its present size. Water from El Cajon or from San Luis Rey would have served the same purpose and exerted the same happy influence on the growth of population and stability of values. Since the city had failed to adopt a project of its own, it was very fortunate to possess a capitalist able and willing to meet its needs upon reasonable terms at a crucial moment in its history.

Return to Books.

HISTORY OF SAN DIEGO

Main Page

Author’s Foreword

Introduction: The Historical Pre-Eminence of San Diego

PART ONE: Period of Discovery and Mission Rule

- The Spanish Explorers

- Beginning of the Mission Epoch

- The Taming of the Indian

- The Day of Mission Greatness

- The End of Franciscan Rule

Priests of San Diego Mission

PART TWO: When Old Town Was San Diego

- Life on Presidio Hill Under the Spanish Flag

List of Spanish and Mexican commandants - Beginnings of Agriculture and Commerce

List of Ranchos in San Diego County - Political Life in Mexican Days

- Early Homes, Visitors and Families

- Pleasant Memories of Social Life

- Prominent Spanish Families

- The Indians’ Relations With the Settlers

List of Mission Indian Lands - San Diego in the Mexican War

- Public Affairs After the War

- Accounts of Early Visitors and Settlers

- Annals of the Close of Old San Diego

- American Families of the Early Time

- The Journalism of Old San Diego

- Abortive Attempt to Establish New San Diego

PART THREE: The Horton Period

- The Founder of the Modern City

- Horton’s Own Story

- Early Railroad Efforts, Including the Texas and Pacific

- San Diego’s First Boom

- Some Aspects of Social Life

PART FOUR: Period of “The Great Boom”

PART FIVE: The Last Two Decades

- Local Annals, After the Boom

- Political Affairs and Municipal Campaigns

- Later Journalism and Literature [new material in second edition]

- The Disaster to the Bennington

- The Twentieth Century Days

- John D. Spreckels Solves the Railroad Problem

PART SIX: Institutions of Civic Life

- Churches and Religious Life

- Schools and Education

- Records of the Bench and Bar

- Growth of the Medical Profession

- The Public Library

- Story of the City Parks

- The Chamber of Commerce

- Banks and Banking

- Secret, Fraternal and Other Societies

- Account of the Fire Department

PART SEVEN: Miscellaneous Topics

- History of the San Diego Climate

- San Diego Bay, Harbor and River

- Governmental Activities

- The Suburbs of San Diego

Political Roster, City of San Diego

Political Roster, San Diego County